The San Luis Obispo International Film Festival has given SLO Review the opportunity to review some of the narrative and documentary feature films on its 2024 program schedule. Follow the links to purchase tickets to see these notable films for yourself.

A Stunning Documentary Set in BC Resonates in SLO County

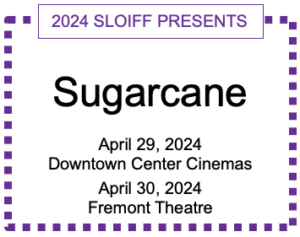

Sugarcane, a stunning documentary from Julian Brave NoiseCat and Emily Kassie screening at the SLO International Film Festival later this month, tells a story set in British Columbia. But it resonates even here in San Luis Obispo County.

Rosario Cooper, the last speaker of the dialect of her language (referred to by scholars as Obispeño Chumash), died in Lopez Canyon, east of Arroyo Grande, in 1917. But her language was recorded and so survives. Many Chumash—the yak titʸu titʸu yak tiłhini (ytt) people—went to the Sherman Indian School in Riverside, where they were punished for speaking Cooper’s language.

So were the children of the Williams Lake First Nations of British Columbia. They were sent to the St. Joseph Mission Residential School, which closed in 1981. Sugarcane (the film takes its name from a nearby reservation) depicts punishments at the school that are unbelievable for little boys and girls. A barn was used to tie up miscreant students and whip them. Six-year-olds who talked in class were made to hold oversized Bibles, the weight of cinderblocks, over their heads for an hour.

The intent of schools like these, as the film points out, was to annihilate the Indian.

But it wasn’t enough to annihilate living Native Americans—the little boys who learned manual labor and wood shop and the little girls who learned baking and canning and dusting. Even the dead have suffered.

In the 1880s, a ytt burial ground that lay in the path of the Pacific Coast Railroad near Avila Beach was obliterated. In the 1890s, crews installing a new water main beneath Chorro Street, near the Mission in San Luis Obispo, did the same to the remains of the indigenous people buried there.

Near the St. Joseph School in British Columbia, a preliminary scan from ground-penetrating radar revealed at least 93 potential burials, likely the bones of residential school students whose names will never be known. One former student remembered nuns carrying the body of a newborn infant inside a shoebox down to the school incinerator.

The most stunning sound is a long moment of silence when a tribal elder confronts the Superior General of the Mission Oblates with the story of three generations of physical and sexual abuse.”

Julian Brave NoiseCat’s father, Ed Archie NoiseCat, was luckier. A dairyman found him, soon after his birth, in an ice-cream carton hidden inside a dumpster. What makes the film powerful is the story of reconciliation between the filmmaker and his father, who had been abandoned by a mother who was ashamed to bear him.

Why was she ashamed? The film depicts another former student who, at his wife’s behest, has a DNA search done. He is an indigenous Canadian, but his DNA reveals that he is 50% Irish and 5% Scots, and a match is made with a distant cousin named McGrath.

Father McGrath was a teacher at the school. The same priest who heard his confession, one former student remembered, pulled him out of his bed in the boys’ dormitory at night.

Every year, in the first week of September, a cattle truck arrived at “The Rez” to take the children back to school. Parents had to drag some of those students, crying and shrieking, to the waiting truck.

In the late 1940s, the ytt children at the Sherman School in Riverside were summarily dismissed and replaced by Navajo children. They were no longer wanted. Neither were the children whose parentage, thanks to the Oblate fathers and brothers, were partly White. They weren’t wanted by either world, Native American or White.

This is a sobering film. It is not hopeless. The grace with which the two NoiseCats find healing is Sugarcane’s pivot, and the courage with which an indomitable investigator, Charlene Belleau, pursues the fates of the missing children and the priests who abused them is remindful of another powerful film about a similar subject, Spotlight.

It’s not incongruous to call Sugarcane a beautiful film: Dust mites dance in a shaft of sunlight, Native American horsemen pivot together to run down a hillside, rain-slick roads penetrate thick stands of pine. Above the little Mission cemetery is a statue of Mary, Queen of Heaven, the marble turning mossy. The same statue, draped softly in snow, reappears later in the film, and it is beautiful. Many indigenous people remain Catholic, to the point of defending their churches in the wake of a spate of arson fires set as retribution as more and more unmarked graves were revealed across Canada.

The sounds, too, are evocative: a horse pulling grass just beyond the cemetery fence, crackling embers as men prepare a sweat lodge, a spade hitting the ground and striking wood, the harsh clank as a gate flies open for a bronco and rider at the Fort Williams Stampede, the cooing of doves within the tragic barn where little boys were once whipped.

The most stunning sound is a long moment of silence when a tribal elder confronts the Superior General of the Mission Oblates with the story of three generations of physical and sexual abuse. The priest is numb, and the filmmakers allow his silent hurt to fill the space.

Near the film’s end, Ed Archie kneels in the way boys once did in what were called “Indian Schools” across the United States and Canada. They did so to prepare for the switch.

But this is what happens instead: Julian Brave NoiseCat gently waves an eagle feather above his father’s head and then brushes it along his body in a healing ceremony. It is a moment of redemption that the Mission Oblates had no power to confer.

:: Jim Gregory

The screening of Sugarcane (run time 107 minutes) at the SLO International Film Festival is sponsored by Mona and Gordon Jennings.