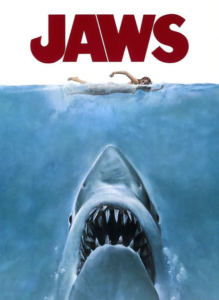

Jaws was scheduled at the SLO Film Center/Palm Theatre July 11-12, 2024.

Younger movie fans who are used to seeing lame Jaws rip-offs might not appreciate what a game-changer the original film was when it came out in 1975.

In truth, few movies have ever been as influential.

Not only did Jaws receive something few horror movies ever do (an Oscar nomination for Best Picture), and not only did it skyrocket the career of young Steven Spielberg (who would go on to become the highest-grossing movie director of all time), it launched the era of the summer blockbuster. Before Jaws, movies with big box-office potential debuted in different seasons (e.g. The Godfather in March 1972 and The Exorcist in December 1973).

After Jaws became the number-one blockbuster of all time, summer became the prime movie-going season. The Omen (June 1976), Star Wars (May 1977), Alien (May 1979) and many other hits soon followed in the wake of Jaws’s summer success.

Add in the movie’s temporal setting—the days just before and after the Fourth of July—and the SLO Film Center’s mid-July presentation of Jaws at the Palm Theatre couldn’t be more appropriate.

Besides creating a new summer movie season, the film re-invented the release pattern for big-event movies.”

Besides creating a new summer movie season, the film re-invented the release pattern for big-event movies. Instead of opening in a few theaters, or just in major cities, so that positive reviews and word-of-mouth referrals could give good movies time to “find” their audience one geographic region at a time, Jaws opened in more than 400 theaters simultaneously in tandem with a nation-wide TV-advertising blitz.

The studio’s goal was not to build a steadily risi ng surge of attention, but rather to instantly generate an overwhelming must-see juggernaut that had to be experienced immediately. And experienced live, too, as Jaws eventually became an actual attraction at Universal Studios. This was a movie too big for mere theaters.

ng surge of attention, but rather to instantly generate an overwhelming must-see juggernaut that had to be experienced immediately. And experienced live, too, as Jaws eventually became an actual attraction at Universal Studios. This was a movie too big for mere theaters.

Movies ever since have tried to emulate its impact and success, but not all of these pretenders have what Jaws does: a plot structure that disrupts expectations, an inventive young director working at the top of his game, and one of Hollywood’s most suspenseful musical themes.

The plot follows the classic three-part structure used for centuries in the theater. A situation is introduced, complications follow, and there’s a compelling resolution. But if the formula is ancient, the presentation felt new in 1975.

Jaws famously kicks off with a savage killing that taps into fundamental terrors. The movie is lethal from the get-go, like a roller coaster that starts by rocketing its riders toward sharp curves and steep plunges.

As a temporary respite from the thrills, the movie includes some bureaucratic disarray. The town’s leaders try to counter their sudden tourist-repelling infamy with distractions and a cover-up scheme involving another, smaller shark they’ve happened to kill. Further attacks by the real, much bigger shark quickly negate their plan.

Once the three principals take to the ocean in the second half to battle the beast, the movie is stripped down to a fight for survival, a fight so brutal that even their boat, the Orca, is completely destroyed.

Surprisingly, the least likely hero survives. The experienced seadog Quint (Robert Shaw) runs out of time-tested tricks and gets devoured. The sharp scientist Hooper (Richard Dreyfuss) relies on new technology that completely fails him. It’s the aquaphobic police chief Brody (Roy Scheider) who utilizes quick-thinking improvisation and succeeds with the help of an old-school rifle.

Notice that the terror is pure and uncomplicated by any political themes. There are no ecological warnings, for instance, no industrial mishap that has let this monster loose. There are no lessons about dealing with sharks that anyone could apply later, other than what not to do. Based on what we see, basically the best advice is to avoid ocean swimming in the first place.

Spielberg seems to know just what the audience wants at any given moment.”

What makes the fast-moving plot even more effective is that the mechanical shark used for filming was rarely working and so couldn’t actually be shown. In fact, in the first two-thirds of this two-hour movie, the shark is only glimpsed in pieces (a fin here, a snout there) for a total of 13 seconds, and by the end its total screen time has added up to fewer than five minutes (only about four percent of the movie).

Delayed reveals intensify many great horror movies, obviously, including different versions of The Phantom of the Opera, The Fly (1958), and on to Predator (1987) and beyond. In Jaws, the suspense steadily builds in the viewer’s mind as the unseen threat gets larger and smarter, and those imagined teeth get longer and sharper.

Though the long, difficult shoot on Martha’s Vineyard went way over budget and over schedule, director Spielberg seems to be working confidently all throughout the movie.

Though the long, difficult shoot on Martha’s Vineyard went way over budget and over schedule, director Spielberg seems to be working confidently all throughout the movie.

Chucking out some of the book’s unseemly episodes—like the tacky affair between Hooper and the chief’s wife—and adding a more audience-pleasing finale than the book’s ending that killed Hooper and let the shark expire from exhaustion, Spielberg seems to know just what the audience wants at any given moment.

Throughout, Spielberg supplements the visceral, heart-pounding story with lighter moments. For instance, he incorporates comic relief to relieve some of the tension.

“You’re gonna need a bigger boat,” says Brody when he sees the shark’s gaping jaws up close for the first time.

“He ate the light” is Hooper’s nervous joke when the boat’s power goes out.

Spielberg also includes some riveting historical perspective about the real-life tragedy of the U.S.S. Indianapolis before he fully unleashes the shark.

Perhaps Spielberg’s most inspired choice was to place his camera at water level, a technique that other directors quickly copied. Scene after scene is shown with the camera right where the victims are splashing, splitting the screen horizontally between sky and ocean. This way it’s not just the on-screen victims who are being attacked; it’s the audience that’s treading water while the unseen shark ambushes them.

Spielberg also moves his camera underwater like it is the shark, showing the audience what the predator sees as it maneuvers toward its helpless victims.

Ultimately, the success of Jaws was the result of a perfect blend of story, ideas, and technique.”

The ominous music by John Williams dramatically amplifies the suspense. His simple two-note theme (dun-DUN, dun-DUN) starts deep and slow but adrenalizes higher and faster as the shark approaches, exploding into a frenzy at the moment of ferocious violence.

Williams’s Oscar-winning music is now one of the most recognizable movie themes in history. Rarely has camera technique matched music technique so effectively.

Ultimately, the success of Jaws was the result of a perfect blend of story, ideas, and technique. Jaws quickly became the all-time champion in ticket sales as audiences returned to see it again and again. Increasingly feeble sequels followed—up to Jaws 4—and unimaginative imitators tried to duplicate its success with swarms of killer fish, big bugs, and other featured creatures.

All these efforts might have made money, but they didn’t make history. Jaws did, because it was first, and it’s still the best.