The Phoenician Scheme: the story of a father and daughter’s love—with complimentary hand grenades!

The latest and very ambitious offering from director and auteur Wes Anderson seems to have confused audiences and critics. Its reception has been generally positive (a subtly volatile designation), but with lots of unwarranted focus on the film’s “quirkiness.” This word is a favorite when discussing Anderson’s films and has been used by some as an easy way to dismiss them, but it seems many of my fellow critics have lost the ability to see beneath the surface.

The Phoenician Scheme is highly stylized, with rich attention to detail and a star-powered cast of, okay, quirky characters, but to dismiss the film at that level and move on makes me wonder if my peers have been spending too much time on Instagram and TikTok.

The film requires thought and attention, and for those who can watch it mindfully, there is an important story woven into its baroque veil that focuses on family, parenthood, and most importantly, the rocky but sweet father/daughter relationship at the plot’s core. Ultimately, we get a strange tale of redemption with an ending that defies viewers’ expectations (and probably confounds some critics).

Deep into the story of Anderson’s new film, we are gifted a revelation that can almost be overlooked. In a conversation between Professor Bjorn (Michael Cera) and novice nun Sister Liesl (a command performance by Mia Threapleton), Bjorn is tapping his fingers, and Liesl recognizes it as Morse Code.

Deep into the story of Anderson’s new film, we are gifted a revelation that can almost be overlooked. In a conversation between Professor Bjorn (Michael Cera) and novice nun Sister Liesl (a command performance by Mia Threapleton), Bjorn is tapping his fingers, and Liesl recognizes it as Morse Code.

The perceptive Liesl explains that she worked in the special collections at her convent’s library, where she learned to decipher Latin and Greek codices and medieval manuscripts. Her formation as a Roman Catholic nun has given her a stable base and a keen insight into human relations. Just as the movie is a codex that needs deciphering by the audience, so her father, Anatole “Zsa-Zsa” Korda (Benicio Del Toro) needs to be deciphered by Liesl to solve the narrative’s major dilemmas, not to mention those of Korda’s endangered life and soul.

This elaborate film reflects on family (as do many of Anderson’s films), and like The Royal Tenenbaums, its focus is a father’s relationship with his children—most significantly, his sole daughter whom he tried to save from the world’s troubles (mainly, boys) by putting her in a convent at age five. The unforeseen effect of this decision of years past is the formation of his daughter into a strong character with devoutly religious, spiritual, and moral perspectives about the world. It has also given her a strong desire for justice and an empathetic spirit of forgiveness. She becomes the unexpected variable in the story of Korda’s life, and ultimately the redemptive force in his world and—most importantly—his family.

Loosely based on Armenian oil tycoon and international business magnate Calouste Gulbenkian (though it’s difficult to overlook parallels to Elon Musk as well), Korda is the world’s richest man. His ruthless rise to wealth and power has made him many enemies, including world governments and members of his own family.

Korda has summoned Liesl from the convent so that she, rather than his nine sons (all younger than her), is to be named his successor and sole heir. Liesl desires to remain a nun, but decides to go along with Korda, seeing an opportunity to do great good with the resources that will be at her disposal. She is perceptive and instantly sees the desolation of Korda’s life. Right away, she is intrigued by “this friendless man” and notes the absence of any kind of love in his life, and she works to create a family community.

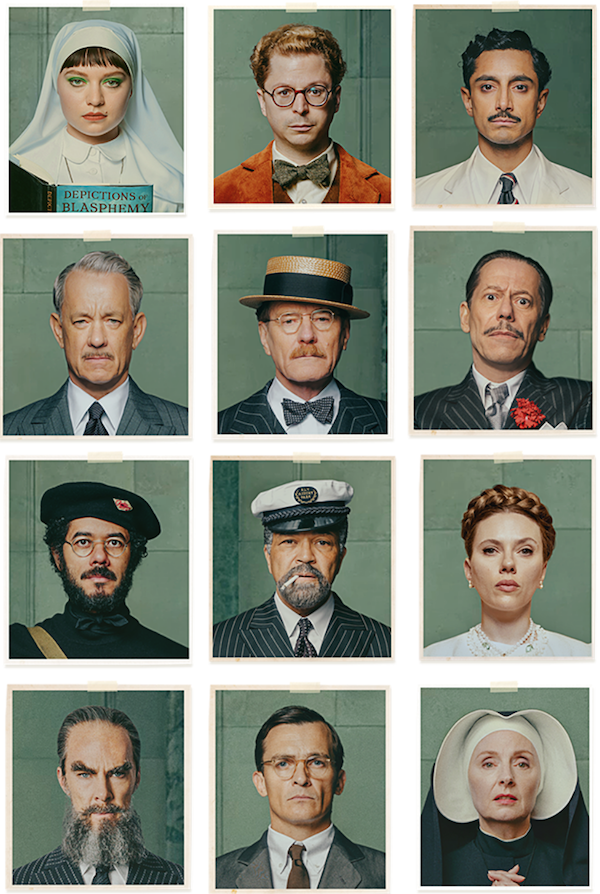

The title of the movie refers to Korda’s most ambitious and greatest business venture. It involves enslaving the entire population of Phoenicia to create a massive avenue of commerce throughout the impoverished country, which requires investments from several sources. The movie becomes a world-hopping adventure as Korda, Liesl, and Bjorn (acting as Korda’s assistant) visit a succession of idiosyncratic characters in the form of former associates, business partners, and relatives (a collection of A-List cameos: Riz Ahmed, Tom Hanks, Bryan Cranston, Mathieu Almaric, Jeffrey Wright, Scarlett Johansson, and Benedict Cumberbatch). His calling card seems to be the offer of the afore-mentioned hand grenades.

The title of the movie refers to Korda’s most ambitious and greatest business venture. It involves enslaving the entire population of Phoenicia to create a massive avenue of commerce throughout the impoverished country, which requires investments from several sources. The movie becomes a world-hopping adventure as Korda, Liesl, and Bjorn (acting as Korda’s assistant) visit a succession of idiosyncratic characters in the form of former associates, business partners, and relatives (a collection of A-List cameos: Riz Ahmed, Tom Hanks, Bryan Cranston, Mathieu Almaric, Jeffrey Wright, Scarlett Johansson, and Benedict Cumberbatch). His calling card seems to be the offer of the afore-mentioned hand grenades.

On this journey, the three of them bond. Liesl begins to learn about her father (keep watch for the book title Questionable Authenticity). Korda’s father was distant and disassociated, and the high point of Korda’s week as a boy was to dine and live with the staff who taught him how to be a proficient cook and dish washer (important information for later in the film). A turning point in the story is when Korda confesses to betraying those staff members to his father.

Korda suffers (and survives) frequent assassination attempts, and recognizes many of the assassins as former employees. Attempted bombings and poisonings are commonplace. He survives being shot by a communist revolutionary when he takes a bullet for night club owner Marseille Bob (Mathieu Almaric)—shades of Casablanca. Taking the bullet does not seem completely intentional, but it is one of his first selfless acts. He survives drowning in quicksand (okay, not an actual attempt on his life, but another near-death experience).

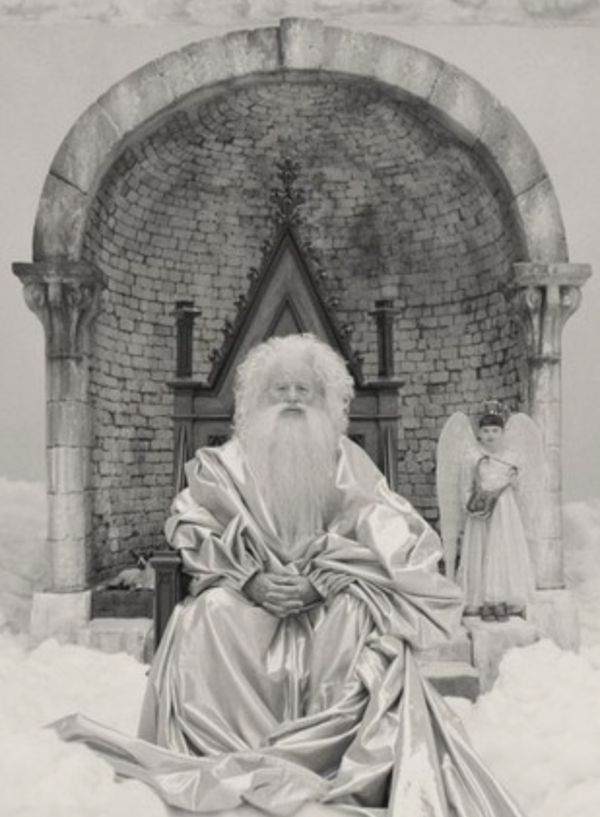

While in the lapses of consciousnesses resulting from his close calls with eternity, Korda has what he calls “visions.” These black and white sequences can be confusing at first, but are clearly scenes of an afterlife and of heavenly judgment being levied on a strangely bearded and biblical-looking Korda.

In his first vision, he turns to the spirit of his grandmother beside him and asks, “What are you doing here?” Her face slowly turns to him blankly, and she gives the chilling response, “I don’t know you.” We feel Korda’s complete familial alienation.

The heavenly court gives us some choice actors: Willem Dafoe plays an advocate, and you’ll get a kick out of Anderson regular Bill Murray’s divine cameo. It is here that Korda learns that Liesl may not be his biological daughter and that enslaving an entire populace is “damnable,” echoing what Liesl has told him.

The heavenly court gives us some choice actors: Willem Dafoe plays an advocate, and you’ll get a kick out of Anderson regular Bill Murray’s divine cameo. It is here that Korda learns that Liesl may not be his biological daughter and that enslaving an entire populace is “damnable,” echoing what Liesl has told him.

Due to his increasingly imperiled state, his visions, and the teetering Phoenician Scheme, Korda converts to Catholicism, and we witness his further transformation when he makes a heartful request of Liesl: if they find out she is not his biological daughter, can he adopt her?

The movie abounds with references to and symbols of afterlife and immortality. In one scene in the Phoenician desert we witness Bjorn cheering on a dung beetle pushing its ball of dung; ancient Egyptians understood these beetles (scarabs) to be symbols of everlasting life.

The movie’s climax occurs at the Desert Oasis Palace Hotel (my favorite location of the entire film), which presents like a spacious tomb and mortuary temple from ancient Egypt. It’s a vast and intricately designed edifice complete with grand columns, statues of Anubis, and rows of hieroglyphs on the walls (even in the elevators!). It is here that Korda confronts his evil half-brother (“He’s not human. He’s biblical.”), a gaunt Rasputin in a business suit played most sinisterly by Cumberbatch. The confrontation peaks with a physical fight of Three Stooges proportions.

In one of the last black and white afterlife scenes, we see Korda and Liesl placing the Anubis-headed canopic urn containing his estranged father’s ashes into a pyramid—a fatherly reconciliation even in Korda’s vision state.

Without spoiling the ending, Korda and Liesl begin to respect and understand each other through their crazy quest, becoming closer as father and daughter. He needs her love so deeply to save his humanity, just as she needs his love for identity, community, and family. We finally arrive at scenes of father, daughter, and sons together at meals, saying a traditional grace.

Some viewers and critics may be put off by the film’s religious themes and overtones, but Anderson does not handle these powerful themes lightly or blindly. There is humility and even healthy doubts (Liesl says she actually pretends that God responds to her petitions and then does what she thinks He would want: “It’s usually common sense.”). Some may simply expect bizarre comedy—and the film does provide for ample laughter with its deadpan humor.

A film like The Phoenician Scheme challenges an audience, and we can and should rise to that challenge. While we don’t have to be on the level of Sister Liesl deciphering ancient codices, with a little mindful attention, our yield of understanding can be much richer.

Our country and culture enable the growth and creation of great artists, writers, and film directors. Films by a careful director like Anderson require a leap of faith. There is so much to this film recommending you take the time to see it—a work of this construction, like Korda’s Phoenician Scheme itself, is complex and multi-faceted with meaning and reference. Look into and through the quirkiness and the ornate aesthetics, the absurdist comedy and grand vistas, and you’ll see a touching story of a father trying to connect with a daughter (and eventually, his sons).

Editor’s Note: The Phoenician Scheme is now playing at The SLO Film Center at the Palm Theatre.