The Brutalist—a three-part, three-and-a-half-hour film depicting the life of a Hungarian-Jewish immigrant architect—covers a lot of ground.

It starts with his entry into the United States (fresh from the Holocaust), then moves on to his work as a steel laborer and later as a designer of a major project for a rich American industrialist. He encounters setbacks, endures his and his family’s afflictions, and finally emerges as a world-recognized architect and proponent of a style known today as Brutalism.

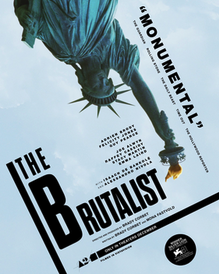

Adrien Brody portrays the architect László Tóth, Felicity Jones is his wife Erzsébet, and Guy Pearce is his American patron Harrison Van Buren. The film’s story and imagery illustrate Tóth’s rises and falls, beginning with his arrival in New York as he observes an upside-down Statue of Liberty and then when he is shown with fellow immigrants, each bearing a large number on a placard around their necks (Tóth was imprisoned earlier in a Nazi camp).

Adrien Brody portrays the architect László Tóth, Felicity Jones is his wife Erzsébet, and Guy Pearce is his American patron Harrison Van Buren. The film’s story and imagery illustrate Tóth’s rises and falls, beginning with his arrival in New York as he observes an upside-down Statue of Liberty and then when he is shown with fellow immigrants, each bearing a large number on a placard around their necks (Tóth was imprisoned earlier in a Nazi camp).

Xenophobic themes run throughout the film. Tóth soon meets a cousin who has changed his ethnic name to a more Waspy one, explaining it is good for his business. The cousin’s Early American furniture company is building casework for a library in the home of Van Buren, and when Tóth takes control his design turns out to be the most beautiful of all of Tóth’s designs throughout the film (and the most relatable, I expect, to the viewer). Tóth’s modernist design impresses Van Buren enough to hire the architect for a major community building on a hill outside of Philadelphia.

Soon, Van Buren modifies Tóth’s design for the community center, and then the industrialist stops the project altogether. The hill with its construction cranes looks like Calvary with crosses.

This pattern—of hopeful expectation soon dashed—is constant throughout the film. Scenes of light to dark and dark to light, health to illness and illness to health, isolation to family and family to isolation, are repeated. The pendulum of a grandfather clock repeatedly swings from light to dark and back again.

The Brutalist is well acted and full of angst, hope, and disappointment.”

Pain is graphically depicted through Erzsébet Tóth’s scoliosis and László Tóth’s drug addictions and later sexual abuse. Jones is convincing as a woman who suffers her disease and her husband’s dreams, and Brody gives a powerful portrayal of a tormented artist. Pearce gives a great performance as a rich, selfish, narrow oligarch whose control dominates Tóth and his work.

The film’s first part covers the years 1947 to 1952, the second 1953 to 1960, and the third is a short (and strangely added) epilogue set in 1980 at a ceremony where Tóth is honored for his substantial work in the Brutalist style—represented by exhibits of Van Buren’s architectural project, now completed. It is likely that only architects of the 1960s will appreciate these blank, over-scaled, inhumane, concrete behemoths. Tóth’s niece repeats a remark he is supposed to have made earlier, “It is not about the journey, but about the destination,” as the film ironically pans to an aged, bent, and gray László Tóth.

Director Brady Corbet filmed the movie in Vistavision, a wide screen, horizontal format first developed in the 1950s which allows broad views both of outdoor scenes as well as closeups of Adrien Brody’s nose—which has never seemed so large.

The Brutalist is well acted and full of angst, hope, and disappointment. As you endure the film’s length (with one well-placed intermission), try to convince yourself that it’s about the destination. This journey isn’t The Sound of Music.

Editor’s Note: The Brutalist is now playing at the Bay Theatre in Morro Bay.